Vermont’s legislature has long emphasized protecting tenants from losing their housing, even permitting renters to withhold payment when landlords fail to meet habitability standards. Vermont property law, however, draws two very different pictures of housing rights. Tenants who fall behind on rent are shielded by multiple statutory protections before a landlord can regain possession. By contrast, property owners who fall behind on taxes face the certainty that municipalities — backed by state law — will collect, even if it means selling off the property itself.

The contrast raises a fundamental question: if tenants are entitled to extended protection from eviction and expectations of adequate services, shouldn’t property owners be entitled to the same when the creditor is the state? Or more bluntly: do property owners in Vermont truly own their property, or are they tenants of the state, paying rent in the form of property taxes?

Tenant vs. Landlord: The Eviction Process

Under Vermont’s Residential Rental Agreements Act (9 V.S.A. § 4451 et seq.), a landlord may terminate a tenancy for nonpayment of rent by giving the tenant 14 days’ written notice. If the tenant pays in full during that time, the tenancy continues as if nothing happened.

If payment is not made, the landlord must file an ejectment action in court. Vermont law forbids “self-help” evictions — landlords cannot change locks, cut utilities, or deny access to the unit. A writ of possession can only be issued by a judge, and only enforced by the sheriff.

In practice, this means the process can stretch from weeks into months. Tenants can raise defenses, request hearings, and delay proceedings. Even after a judgment, sheriff scheduling can extend the timeline further.

Late fees add little leverage. Vermont law permits them only if spelled out in the rental agreement and only if they reflect the landlord’s actual added costs — for example, bookkeeping or communication expenses. Flat charges or “discounts for early payment” have been struck down by courts as unlawful penalties.

The upshot: landlords may wait months to remove a nonpaying tenant, cannot meaningfully penalize late payment, and often must absorb unrecoverable losses. Even if they win a money judgment, it is the landlord’s responsibility to collect — a process many never succeed at.

Property Owner vs. Municipality: Delinquent Taxes

The system looks very different when the property owner falls behind on taxes. Under 32 V.S.A. § 5252, once taxes are more than one year delinquent, the tax collector may initiate a tax sale — but only after first offering the owner a “reasonable repayment plan”.

If no plan is reached, or if the owner defaults, the town may record a warrant, advertise the property for auction, and provide at least 30 days’ notice to the owner, mortgage holders, and lienholders. Unlike with rent, interest, penalties, and collection costs accrue automatically by statute.

Vermont law does build in protections:

- Owners are entitled to a one-year redemption period following a tax sale, during which they can reclaim the property by paying back taxes plus 1% monthly interest.

- Since 2022, Act 182 has required towns to send an additional VHAP (Vermont Homeowner Assistance Program) notice at least 60 days before a final tax sale notice. If the owner applies, the sale is stayed until the application is resolved.

But the bottom line is clear: the state will collect. If the taxes are not paid, municipalities have authority to auction the property itself, ensuring they are made whole in cash or in assets.

Warranty of Habitability

Tenants and Landlords

- Vermont’s Residential Rental Agreements Act (9 V.S.A. §§ 4457–4458) lays out the warranty of habitability: landlords must provide housing that is safe, clean, and fit for human habitation.

- If a landlord fails to meet those obligations — for example, by neglecting heat, water, or structural safety — tenants can seek inspections, withhold rent, and in some cases use the withheld rent to make necessary repairs.

- Importantly, while a renter can lose their housing through eviction, they don’t lose assets — their personal property remains intact. Renters essentially gain leverage over landlords through the ability to withhold payment without forfeiting ownership.

Property Owners and the State

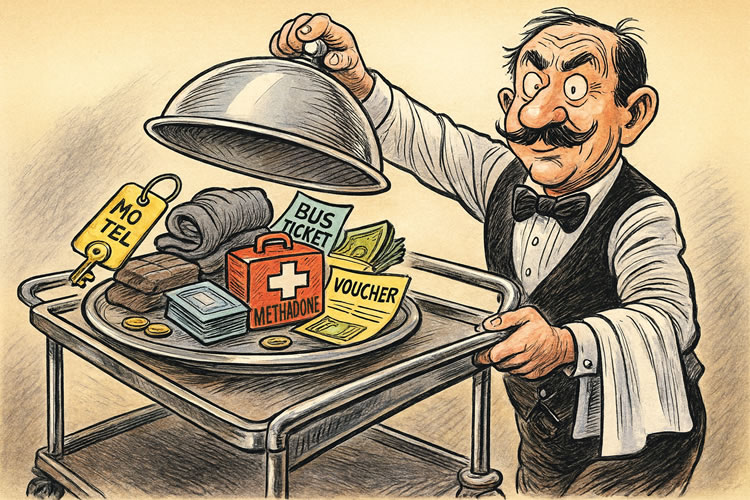

- By contrast, property owners are in a relationship with municipalities and the state that resembles rent: they make recurring payments (property taxes) in exchange for public services like roads, policing, and schools.

- However, there is no warranty of habitability equivalent on the government side. If services falter — potholes go unfilled, policing is understaffed, infrastructure crumbles — property owners cannot withhold taxes.

- Instead, unpaid taxes trigger penalties, liens, and ultimately tax sale of the property. Unlike tenants, property owners stand to lose both their housing and their asset.

Comparison

- The landlord–tenant relationship is voluntary: tenants choose a lease, and if dissatisfied, can move.

- The taxpayer–state relationship is mandatory: while in theory an owner can sell and leave Vermont, the burden of exit is much higher than ending a lease.

- Both landlords and the state rely on payments (rent and taxes) to meet obligations. Yet only landlords face legal consequences if they fail to deliver promised services, while the state enforces payment regardless of its own performance.

🍁 Make a One-Time Contribution — Stand Up for Accountability in Vermont 🍁

Who Bears the Risk?

The contrast is stark.

- Landlords: carry all the risk. If tenants don’t pay, landlords may lose months of income with no guarantee of recovery, while still on the hook for mortgages, upkeep, and taxes.

- The state: bears virtually no risk. It has statutory powers to add fees and interest, negotiate repayment plans, and, if necessary, take the property itself.

Tenants who don’t pay lose only their right to occupy — they walk away without assets but often with months of rent-free occupancy. Landlords who can’t pay property taxes, by contrast, may lose both their income stream and the property itself — a double hit.

Fairness and Standards

It is true that tax foreclosure generally moves slower than tenant eviction. Owners may go a year or more before a tax sale is initiated, and still have a redemption window afterward. Tenants can be evicted more quickly in theory — but only after court proceedings that often drag on much longer in practice.

The difference lies not in timing, but in outcome. The renter loses a place to stay but leaves behind a liability with any assets intact. The property owner stands to lose both.

The state’s position is unique: it is simultaneously the lawmaker, the creditor, and the enforcer. That means it plays by rules that guarantee it will get paid. Landlords, by contrast, operate with limited remedies, smaller resources, and significant exposure.

The Larger Question

The picture that emerges is one of unequal footing. Renters in Vermont are afforded statutory protections, including the ability to withhold rent if housing fails to meet habitability standards. Landlords must absorb the financial risk and deliver safe housing, even when tenants fall behind. Property owners, meanwhile, enter into a mandatory relationship with municipalities where the state holds all the leverage. Delinquent taxes bring automatic penalties, liens, and, if unresolved, the loss of both home and asset through tax sale.

The state recognizes the gravity of renters losing housing and has written law to cushion that outcome. Yet the same legislature accepts without question that delinquent property owners may forfeit not only shelter but ownership itself. Landlords cannot seize a tenant’s property to make themselves whole. Municipalities, by contrast, can seize real estate outright and are guaranteed recovery.

The comparison raises unresolved questions. If tenants may withhold rent when landlords fail to provide safe housing, why is there no parallel right for taxpayers when public services falter? If landlords are held accountable for meeting obligations, should not the state be measured by the same standard? And if the legislature has devoted so much attention to shielding renters from eviction, why has it not extended equal protection to property owners facing the far greater loss of both housing and equity?

The state plainly recognizes the importance of securing its own revenue, yet it does not extend the same recognition to landlords who depend on rent to cover their expenses. Landlords are told to shoulder the risk of nonpayment, while the state ensures recovery with interest and fees. The imbalance is hard to miss.

With the second half of the biennium approaching, these questions may test whether Vermont’s lawmakers view property owners as true owners — or as tenants of the state.

Dave Soulia | FYIVT

You can find FYIVT on YouTube | X(Twitter) | Facebook | Parler (@fyivt) | Gab | Instagram

#fyivt #Vermont #PropertyRights #HousingPolicy

Support Us for as Little as $5 – Get In The Fight!!

Make a Big Impact with $25/month—Become a Premium Supporter!

Join the Top Tier of Supporters with $50/month—Become a SUPER Supporter!

Leave a Reply to Robert FireovidCancel reply