(Editor’s note: We know this one runs long — it’s Part Two of yesterday’s story — but it’s worth every minute. The deeper you read, the clearer the picture becomes of how Vermont’s environmental rules are being written, enforced, and litigated, often by the very same people.)

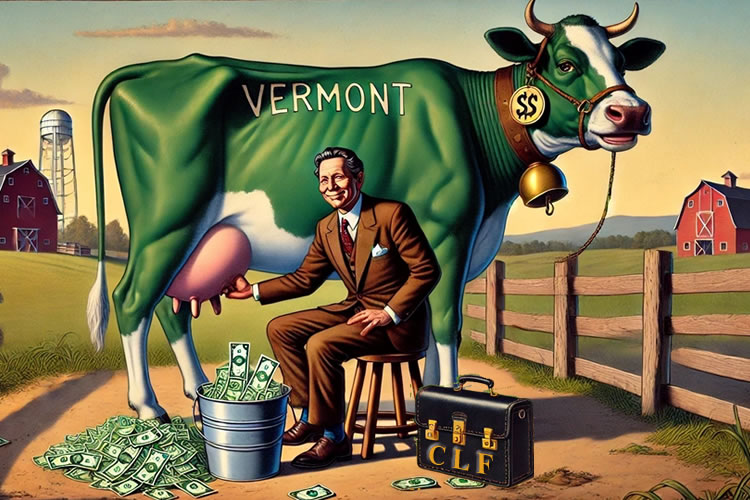

In Vermont, the line between environmental policymaking and courtroom strategy has nearly disappeared. The same advocacy network that helped write the state’s climate and water rules now sues the agencies and farms that follow them—an endless loop of petitions, corrective orders, and consent decrees that leaves little room for either legislators or citizens.

From climate goals to consolidation

The story begins long before the recent lawsuit against Vorsteveld Farm. In 2020, the Vermont Natural Resources Council (VNRC) and the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) championed passage of the Global Warming Solutions Act. The law transformed greenhouse-gas targets into binding mandates and authorized lawsuits against the state if it failed to meet them.

When EPA later pressed Vermont to reduce agricultural emissions, the Agency of Agriculture and the Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) responded with what federal guidance described as “climate-smart intensification.” Fewer farms, more efficient operations. Tile-drain systems, nutrient management plans, manure lagoons—standard conservation practices endorsed by USDA NRCS and EPA alike.

That logic appeared in a Clean Water Initiative webinar hosted by ANR’s Department of Environmental Conservation on July 24, 2024. Officials Nina Gage and Ryan Patch explained how the state’s climate-and-water programs overlapped under the Global Warming Solutions Act:

“It is, in part and parcel to what the EPA recommends… intensification as a strategy to get the same amount of food and more food from the same climate emissions.”

The same presentation noted the steady loss of small dairies across the state—a decline stretching back more than a century. Vermont once had over 10,000 dairy farms; today, fewer than 600 remain. The state’s own climate-mitigation plan effectively endorsed that consolidation.

The petition that forced the plan

Two years earlier, in 2022, VNRC, CLF, and the Lake Champlain Committee petitioned the EPA to declare Vermont out of compliance with the Clean Water Act for failing to issue Concentrated Animal Feeding Operation (CAFO) permits. EPA agreed and ordered the state to prepare a Corrective-Action Plan.

By early 2025, ANR was drafting that plan under EPA oversight. A newsletter from Bethany Sargent, ANR’s water-quality director, acknowledged:

“To date, no CAFO permits have been issued to Vermont farms, and EPA has indicated this is unacceptable.”

The document even credited the three petitioning groups—CLF, VNRC, and LCC—for initiating the federal review.

The presentation before the lawsuit

On January 24, 2025, CLF’s Director of Farm and Food, R. Scott Sanderson, brought a slide deck titled “The Clean Water Act and Agriculture” to the House Agriculture Committee in Montpelier. The PowerPoint, branded with CLF’s logo, outlined the very theory that would later appear in CLF’s lawsuit against Vorsteveld Farm: that tile-drain systems at large dairies constitute “point-source discharges” requiring federal pollution permits.

Legislative transcripts show Sanderson explaining how EPA’s corrective-action order proved ANR’s permitting system inadequate and urging lawmakers to fold those federal standards into Vermont law. The Secretary of ANR, Julie Moore, and her agency were referenced repeatedly as the parties responsible for implementing the fixes.

One lawmaker summarized it bluntly:

“The same petitioners, VNRC and CLF, have been meeting with ANR on potential rule language.”

The day after that presentation, the same CLF deck was distributed statewide as a public PDF. Nine months later, CLF and VNRC filed a Notice of Intent to Sue Vorsteveld Farm—built on the identical legal reasoning.

The “novel” argument that wasn’t

When the lawsuit notice reached the press in October 2025, Secretary Julie Moore told reporters:

“To my knowledge, this is a pretty novel argument in Vermont regarding the management and regulation of tile drainage.”

But the record shows otherwise. Her own agency had been working under an EPA corrective-action plan that incorporated the same argument since 2022. Her staff had attended the July 2024 Clean Water Initiative webinar that cited EPA’s intensification guidance, and her agency was repeatedly named in the January 2025 legislative briefings that carried CLF’s thesis word-for-word.

Calling it “novel” may have been politically convenient. It was not factually correct.

🍁 Make a One-Time Contribution — Stand Up for Accountability in Vermont 🍁

When advocacy becomes administration

By this point, CLF and VNRC occupied every corner of the policymaking triangle:

- Legislative — drafting and promoting the Global Warming Solutions Act and briefing committees on CAFO enforcement;

- Administrative — petitioning EPA and working with ANR on corrective-action language;

- Judicial — filing citizen suits under both the Clean Water Act and the Global Warming Solutions Act.

Each step reinforces the next. Petition leads to federal order; order leads to state plan; plan becomes the basis for litigation; litigation forces the change that couldn’t clear a committee vote. The result is policy by court filing—a process that bypasses the slow machinery of representative government.

The lobbyist–litigator overlap

The same names recur in committee rooms and in court filings.

- Elena Mihaly (CLF vice president & director of the Vermont Advocacy Center — registered Vermont lobbyist) signed the 2024 notice threatening to sue the State under the Global Warming Solutions Act and is the lead voice on the 2025 Vorsteveld notice.

- R. Scott Sanderson (CLF director of Farm & Food — registered Vermont lobbyist) delivered the Jan. 24, 2025 House Agriculture presentation, The Clean Water Act and Agriculture, outlining the same theory later used in the farm lawsuit.

- Mason Overstreet (CLF staff attorney — registered Vermont lobbyist) co-signed the Vorsteveld notice.

- Heather Govern (CLF environmental litigation director) co-signed the Vorsteveld notice.

- Jon Groveman (VNRC policy director — registered Vermont lobbyist) co-signed the notice for VNRC.

Access and advantage. These are not separate worlds. The people lobbying lawmakers and ANR on rule text are the same people filing (or supervising) the lawsuits when those rules or timelines disappoint. The arrangement gives one organization insider access to the policymaking table—and a ready-made plaintiff’s brief if the outcome disappoints.

Concerns over leadership and conflicts

The Vermont Agency of Natural Resources (ANR) sits at the center of both the state’s water-quality enforcement and its uneasy relationship with environmental litigants. Secretary Julie Moore, has been cautious to publicly challenge the federal mandates driving many of these policies — even as those same mandates have become the basis for lawsuits against Vermont farms.

Her position is further complicated by her role as board chair of the Vermont Council on Rural Development (VCRD), a nonprofit that regularly partners with ANR and advocacy organizations including the Conservation Law Foundation (CLF) and the Vermont Natural Resources Council (VNRC) on climate and infrastructure planning.

The cost of circular governance

For farmers, the outcome is not theoretical. The shift from state-level Required Agricultural Practices to federal NPDES permitting could raise compliance costs from a few thousand dollars per year to well over $150,000 for monitoring, laboratory testing, and reporting. The farms most likely to survive are the ones large enough to absorb those costs—the very concentrated operations the state and EPA promoted as climate-efficient only a year ago.

For taxpayers, the loop adds another price tag: endless agency rewrites, consultant contracts, and litigation settlements. Vermont’s environmental budget grows; its agricultural base shrinks.

The democratic deficit

No one elected the Conservation Law Foundation or the Vermont Natural Resources Council. Yet their petitions and lawsuits now dictate how ANR writes rules, how EPA evaluates the state, and how courts compel compliance. Legislators are left reacting to court mandates instead of writing law.

That’s the quiet story behind the noise: Vermont’s environmental governance has migrated from committee rooms to courtrooms. Policy no longer advances through debate and compromise; it advances through litigation and consent decree.

The irony is painful. The same advocates who helped craft the climate-mitigation framework that favored larger, more efficient farms now condemn those farms as polluters. The same state officials who promoted EPA’s “intensification” guidance now claim surprise when that guidance becomes a lawsuit.

If policy can be written in a courtroom faster than it can be debated in committee, what’s left for Vermont’s elected representatives to decide?

Dave Soulia | FYIVT

You can find FYIVT on YouTube | X(Twitter) | Facebook | Parler (@fyivt) | Gab | Instagram

#fyivt #VermontFarms #CleanWaterAct #RegulatoryCapture

Support Us for as Little as $5 – Get In The Fight!!

Make a Big Impact with $25/month—Become a Premium Supporter!

Join the Top Tier of Supporters with $50/month—Become a SUPER Supporter!

Leave a Reply