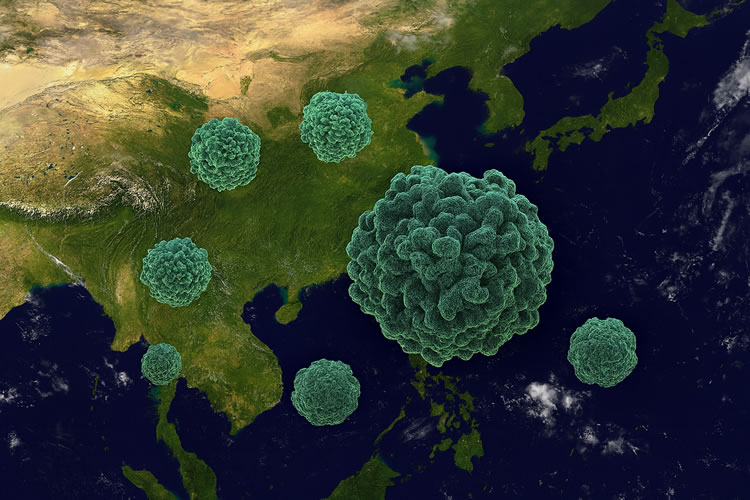

The chikungunya virus is suddenly everywhere in U.S. news — splashed across TV headlines, online feeds, and radio bulletins — after reports of a large outbreak in southern China. It’s China’s first significant surge of the mosquito-borne illness, and the story’s timing has made some people uneasy. Just five years ago, another strange-sounding virus emerged in China and upended the global economy. But chikungunya isn’t COVID, and it doesn’t spread like it. Here’s what’s actually happening, how it’s transmitted, and why Vermonters face virtually no risk. The outbreak is centered in Guangdong Province — China’s far-south coastal region on the South China Sea — and the city of Foshan, roughly 600 miles south of Wuhan.

What It Is

Chikungunya is a viral disease first identified in Africa in the 1950s. It spreads through the bites of Aedes mosquitoes — primarily the Aedes aegypti and the Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito). It is not airborne and cannot spread person-to-person. The only way to catch it is to be bitten by an infected mosquito.

The virus likely reached China through gradual migration via Asia from Africa, moving in mosquito populations and possibly in infected travelers. Guangdong’s hot, humid, low-lying environment already supports the mosquitoes that can carry it — the surprise is not that it can spread there, but that it hasn’t taken hold before now. Chikungunya’s path to China followed a slow, predictable pattern: first moving from Africa into the Indian Ocean region, then spreading into Southeast Asia, and finally arriving in southern China through infected mosquitoes and occasional human travelers.

Symptoms

Most people who catch chikungunya will feel lousy but recover fully. Symptoms appear 3–7 days after a bite and can include:

- Sudden high fever

- Severe joint pain (especially in hands, wrists, ankles, and feet)

- Muscle aches

- Rash

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Nausea

Most cases clear in 1–2 weeks, though joint pain can linger for months in some cases. Deaths are rare and usually limited to infants, the elderly, or those with major health problems.

The Situation in China

China is throwing a lot at this outbreak:

- Pesticide spraying by truck and drone

- Distribution of mosquito nets

- Efforts to remove standing water where mosquitoes breed

- Some quarantines and health checks for confirmed cases

The outbreak is not on track to become global — chikungunya doesn’t have pandemic potential like COVID. Without mosquitoes to pass it along, the virus stops cold.

🍁 Make a One-Time Contribution — Stand Up for Accountability in Vermont 🍁

Vermont’s Connection — and Why It’s Not a Big Risk Here

The Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) — one of the species that can carry chikungunya — has been found in southern Vermont for decades. But the virus has never been locally transmitted here. In the U.S., the last known locally acquired chikungunya cases were a decade ago in Florida and Texas — both hot, humid environments where the mosquitoes thrive year-round. In 2014, Florida recorded a small cluster of locally acquired cases, followed by Texas in 2015 with another handful. Since 2019, there have been no new local cases anywhere in the U.S. Meanwhile, chikungunya has been entrenched in parts of Central and South America since 2013, fueling occasional introductions into the southern U.S.

While those were the last locally acquired cases, imported infections still appear in the U.S. every year. According to CDC data, all confirmed cases in recent years have been travel-related, with 2025 already seeing 47 total cases — none of them from local mosquito transmission. These numbers reflect the virus being brought in by travelers returning from affected regions, not ongoing circulation in U.S. mosquito populations.

That said, Vermont’s climate — especially the cold winters and inconsistent summer standing water — limits its population and the ability of the virus to establish here. Even in southern counties like Windham, where Aedes albopictus is most likely to be found, there have been no recorded local cases of chikungunya.

And while mosquito season can be bad in wet years, Vermont has seen extended dry spells in recent summers. Flash floods can actually reduce mosquito numbers by flushing larvae out of breeding pools. The past couple of weeks of hot, dry weather likely knocked down mosquito activity even more.

The Bottom Line

This is not COVID. It doesn’t spread through the air or human contact — only by infected mosquitoes.

You won’t die from it in all but the rarest circumstances, but you’ll feel miserable for a week or two.

The Guangdong outbreak is a first for China at this scale, but not unexpected given the climate and mosquito presence there.

Vermont has one of the mosquitoes that can carry chikungunya, but the chances of a local outbreak are extremely low — and far more likely you’ll be hit by a meteor first. It’s holding steady in the warmer parts of the Americas, but it’s not marching north toward Vermont anytime soon.

Best protection anywhere? Avoid mosquito bites: use repellent, wear long sleeves, and remove standing water. And keep your eyes open for meteors.

Dave Soulia | FYIVT

You can find FYIVT on YouTube | X(Twitter) | Facebook | Parler (@fyivt) | Gab | Instagram

#fyivt #Vermont #China #Chikungunya

Support Us for as Little as $5 – Get In The Fight!!

Make a Big Impact with $25/month—Become a Premium Supporter!

Join the Top Tier of Supporters with $50/month—Become a SUPER Supporter!

Leave a Reply